A buyer's guide to collecting Japanese works of art

The arts and Japan have been a source of fascination in the West since the first Portuguese traders arrived on her shores in the 1500s. Today's collecting market is the result of more than our centuries of contact.

A midnight-blue ground Satsuma vase signed with a tablet for the Kinkozan studio in Kyoto. Sold for £1400 at Sworders in November 2022.

The Japanese art collecting umbrella covers a wide range of art styles and media from the pottery vessels of the pre-historic Jomon period to present-day anime and manga.

However much of what appears on the international auction market today comes from three distinct periods – the Momayama (1568-1600), the Edo (1603-1867) and the Meiji restoration (1868-1912).

It was during these centuries that the traditional crafts of carving, metalworking, lacquer working, embroidery and woodblock printing reached a peak and when powerful western ideas of Japan and Japanese art were formed.

The collecting of Japanese art in the west began in the Momayama and the early Edo epochs. The first European merchants bought home porcelain, so-called Nanban lacquer wares, silks, swords and armour. Particularly highly prized were the range of export porcelain from the kilns at Arita - kakiemon, Chinese-derived blue and white and imari - plus the rarefied nabeshima wares made for the domestic market. All are eagerly collected today.

It was during the Edo period that Japan had minimal contact with the outside world. However, in a period of domestic peace and stability, the arts flourished. By the mid 18th century, Edo (modern-day Tokyo) was the largest city in the world and some of the classic collecting genres – sword fittings, netsuke, inro and woodblock prints or ukiyo-e emerged with the rise of popular culture.

Few can fail to be charmed by netsuke and ojime (the toggles used to secure a kimono sash) and inro, the small boxes that hung from them). Prices vary according to the artist, the condition, the quality of the carving, the rarity of the subject – plus the material. With the UK ban on the sale of most antique ivory, many collectors are turning towards stag antler and wood netsuke.

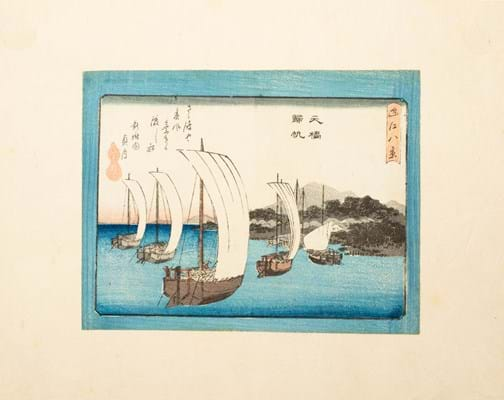

Leading exponents of Japanese woodblock printing such as Utamaro, Hiroshige, Hokusai are now placed in the pantheon of all-time great artists. Evolving across three centuries, the subject matter is vast – first courtesans, actors, warriors and monsters and later landscapes and the natural world – but broadly speaking, the more eminent the artist and the more famous the image, the pricier the work.

Woodblock prints were among the arts of Japan that had most impact on the West in the late 19th century as Japan began to ‘open up’. Under the Meiji restoration (1868-1912) isolationism was replaced by internationalism. An explosion of interest in Japanese art and culture followed.

Meiji works of art reflect this key moment in history, often combining traditional Japanese aesthetics with designs and techniques deemed pleasing to Westerners. Courting a new clientele following the decline of the samurai class and its privileges, former sword makers and armourers applied their exemplary skills and artistry to decorative objects, mostly made for export.

The Myochin family specialised in the production of fully articulated metal animals – the so-called jizai okimono – while the Kyoto firm Komai championed the technique of inlaying gold and silver onto iron.

Cloisonne wares reached the peak of artistic and technological sophistication in this ‘golden age’ period although most pieces offered for sale are of relatively modest value. Meiji art was produced in different quality grades to fit different budgets.

There was a huge increase in the production of Satsuma earthenware that in Western eyes became synonymous with Japanese ceramics. Exhibition quality pieces by the best-known Satsuma studios, capable of the near-perfect execution, minute detail and stylistic brilliance, were made alongside much cheaper mass produced work. After collecting peaks in the late 20th century, collectors can today find good pieces in the low hundreds and exceptional works in four figures.

Value for money is one very good reason to collect Japanese art. In contrast to the buoyancy of the Chinese art market and its exponential growth over two decades, the market for most Japanese works is much quieter. As prices have not moved a great deal in a generation it may be a good time to buy.